We were invited to a party the other day.

“What kind of party?” was the question.

“Dope and the Rolling Stones,” was the answer.

* * * * *

Sticky Fingers is the long-awaited and at times almost forgotten-about latest lp by the Rolling Stones, the greatest something-or-others in the world. It’s the most garish throw-together since Flowers, half of the material dates back over a year, some of it is stupid, and some of it is just plain bad. I play it all the time, and the more I play it, the louder I play it.

* * * * *

The Stones had to deal first with a pop scene that feels dispirited, and with their own absence from it. Zip.

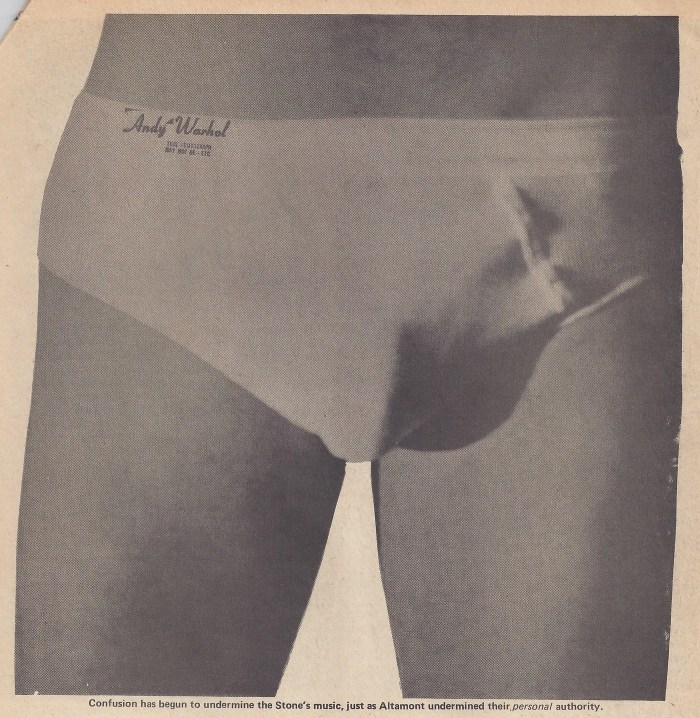

You do look, right? It took Andy Warhol to make people relate to an album cover as directly as they might to the music it contains. The Stones won the first round; they organized the audience around their record, without even making them listen. The lp was stared at and glared at, talked about, passed around, and finally heard. All over the place. It took over the radio.

* * * * *

“Uh, Brown Sugar, how cum

ya taste so gud?

Brown Sugar, just like a

black girl shud?”

Try that on Angela Davis next time you run into her.

The flip side was called “Bitch”.

Disgusting stuff? It was disgusting, not only because it seems uncool this year, but because a lot of women are degraded when they hear the song come off the radio every hour like clockwork, especially when it comes from a group in which they have invested such affection and from which they have received such pleasure. Don’t the Stones have anything left but that regressive drool of the aging fop? Was the stuff they were peddling still worth anything?

A new album by the Rolling Stones is the inevitable soundtrack to the events of the day. It is what is played and what you hear. The real question is whether or not it can carry the weight of those events, without directly addressing them and without betraying them. In the last few years, the ability to carry that weight has been nothing less than the Stones’ claim to a career.

* * * * *

“Brown Sugar” was racist, sexist, it threw me and a lot of other people and took the fun out of hearing it just as if the Stones’ had done “The Ballad of the Green Berets” and meant it. The music went flat as the theme of the song subverted its sound. The radio news broke just as the last notes of “Brown Sugar” faded and I heard Leslie Bacon speaking to a women’s demonstration just before the government put her away:

” …Nothing scares the u.s. government more than women getting together. J. Edgar and the u.s. government are making me a scapegoat for their insane and irrational paranoia & their inability to catch those who bombed the capitol. I am a political prisoner like women in the prisons of amerikan homes, schools, & factories. I think about Angela Davis, Erika Huggins, & Judy Clark a lot, knowing their situation is worse than mine, but still feeling close to them. They are my sisters… I have nothing but contempt for the amerikan government and incredible love for my sisters.”

Those words blew the leer of “Brown Sugar” right off the radio.

* * * * *

But the music was good. My reaction to the words I automatically picked out of the song crippled its power. Still, the radio stayed on and “Brown Sugar” was unavoidable. If what Jagger was singing had no place in my life, there was no way to escape the fact that the music did. The conflict between the Rolling Stones ROCK OUT and so gud just like a black girl shud became absurd.

Then one day as I took a turn “Brown Sugar” started up and I heard Gold Coast slave…

That was all I heard. It threw me off again. I couldn’t make out the rest.

“I remember when I was very young,” said Mick once to Jon Cott, who was interviewing him for Rolling Stone, “this is very serious, I read an article by Fats Domino which has really influenced me. He said ‘you should never sing the lyrics out very clearly.’

“You can really hear ‘I got my thrill on Blueberry Hill,” said Jon.

“Exactly, but that’s the only thing you can hear. Just like you hear ‘I can’t get no satisfaction.’ It’s true what he said’ though. I used to have great fun deciphering lyrics.”

OK, Mick. I like your theory.

But what is this crazy song about?

I asked around. Everybody seemed to know what it was “about” but no one knew what the words were. So finally, just like Mick Jagger, six of us put our heads. up against a pair of speakers and found out.

“Gold Coast slave she’s bound

for cotton fields

Sold in the market

down in New Orleans

Scarred old slaver know it’s

doin’ alright

Hear him whip the women

just around midnight…

Drums beatin’ cold

English blood runs hot…

[what a great line]

“Lady of the house wonders

where it’s gonna stop…

[as we go into an orgy of colonial miscegenation]

“I’m no schoolboy but I

know what I like

You shoulda heard me

just around midnight!”

What I heard was a spectacular and definitive parody and reversal of the anti-woman currency the Stones have used for money all these years, shot through with a weird admission of the racial ambivalence of their own music.

“Brown Sugar” seemed’ to be opening up the seamy side of white sexual fantasies and of white rock and roll, as the Stones used a black man’s music—Chuck Berry’s—to sing an ode to white racism, even including, in a line not quoted, a little black houseboy just to round out the picture.

These fantasies—sexual and racial—come as naturally to the Stones as they do to their audience, and in writing a song set squarely in the colonial past of their own history and set as well in our own country, where racism is anything but history, they capture not only their own roots but our own crime, as it follows us into the present. English rake meets American host.

They take the roles of sexist buccaneers living high off the racial swamp of America, acting out a story too grossly vicious to accept at face value. Their role-playing allows us to see a certain reality and its rejection, in a parody of their own familiar posturings and of our own new sensitivities. It’s a very neat inversion.

Maybe it’s too neat. None of this stuff may be true. Nothing has been able to convince me one way or the other. The leer may be a parody, but is it still a leer? This song seems to have two sides to it, and both… work.

The ambivalence released the music; nothing sounds better and nothing is more exciting to hear. Months after its release Top 40 still has it on the playlist because there is nothing else to play that rocks as well.

The gears of “Brown Sugar” change like a stick-shift Chevy going flat out on an open road and it kicks off the album. As with the two LPs that preceded Sticky Fingers, there is the opening hard rocker with well-buried lyrics, the ancient blues, the country joke, the lyrical statement of resignation, And the big production to close it out. This time around they also tied up the loose ends of their live material, added their version of an old number written for Marianne Faithful and probably recorded more than a year and a half ago, and graced us with three numbers that may actually represent their current musical ideas, all arranged together in the last installment of a trilogy that may have more to do with habit and convenience than vision or inspiration. But then, that’s the thing about rock and roll art. It’s not very artistic.

The structure of Sticky Fingers may have a perfect formal correspondence with Let It Bleed but underneath the albums are altogether different. On the earlier record, it seems to me, things were very very clear: there were those astonishing first and last cuts that held the power of the band both as writers and musicians, a couple of very fine songs, a couple of forgettable performances, and a good deal of fooling around within a genre that both the Stones and their audience had long before defined as limited, but traditional. “Live With Me” or “Let It Bleed” were trivial and fun, the Stones’ version of good-time music.

This time it appears that the Stones’ image of themselves and their understanding of how that image ought to be used—an image which must be made up of the flimsier elements of their “tradition” or whatever one wants to call it—has entered into murky conflict with the power of the Stones’ music, their flair for rock and roll, and their ability to exert a certain defining pressure on our sense of the situations of the day. There seems to be an attempt to satisfy every possible expectation in virtually every song, to touch all bases at once. This kind of confusion, or self-consciousness, has to do with a real uncertainty about what it means, now, to be the Rolling Stones, and the resolution of that uncertainty is what the Stones will have to accomplish with their next few albums. What they have done with this one, though, is another story.

Because of the conflict between music and image the bad moments of this album tend to stand for the album itself, instead of merely fading into the background the way, say, “Country Honk” did on Let It Bleed. “Gotta Move” is a dumb joke and “I Got the Blues” is monumentally contrived, but then, the reference to “Cousin Cocaine” in “Sister Morphine”—which is a great image and a powerful performance—is also a bad joke that almost sinks the song. “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” Part I, is a definition of the music the Stones were born to play, but those lines about “cocaine eyes” and “speed-freak jive” are a contrived attempt to let the listener in on the secret that Mick really knows exactly where it’s at. This sort of insecurity sets up a situation where the fire of Keith Richard’s guitar and the commitment of his singing is fighting off the silliness of Jagger’s pose; and the difference between what can be communicate by this doper cool and a line like “the red ’round your eyes’ shows that you ain’t a child” is the difference in impact between Alvin Lee yelling “I Want To Ball You” and Mick howling “jump right ahead in my web.” The same thing goes for “Moonlight Mile.” The song sets a scene and moves to draw the listener into it, bringing him to a place where he is conscious of his isolation and allowing him to draw real satisfaction from that isolation; the performance has a kind of splendor to it. It takes delicacy to bring this off, and again Mick almost blows it by throwing in a corny line—corny because it’s so “cool” and so “poetic” —about his “head full of snow.” Drugs are so unnecessary to the state of mind and the physical reality Mick is trying to evoke that his cute drug reference—to cocaine of course, gotta wear your hip right on your hip—begins to limit the scope of the song almost before it’s begun. He is holding back his own music, and not on purpose either.

Inevitably, all these coy dope stories fail to even begin to make the kind of vital statements about drugs the Stones have made before in songs like “19th Nervous Breakdown,” “Gimme Shelter,” or “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.” There the Stones were conveying knowledge about a situation instead of merely demonstrating that they were hip to it. The whole idea of the Rolling Stones was that their ability to make strong music and to communicate easily and well could be taken for granted as part of our special social reality. The fact that it was taken for granted, both by us and by the Stones when they made music, did not make their music less valuable but more valuable, and it was an essential part of their authority as a band.

It’s not surprising that this sort of confusion has begun to undermine the Stones’ music, just as Altamont undermined their personal authority. They are in a post-Altamont state just as surely as we are, albeit in a far different way; but their confusion and their self-consciousness about how to make music is another side of our confusion about how to act and how to live. The casual way in which they rattle drugs as if they were maracas does not really exempt them from the responsibilities of doing so any more than the equally casual treatment of the life and death choices implicit in those drugs by much of our own culture exempts that responsibility. But if the confusion of the Stones ultimately destroys their ability to hit a situation straight on, as when the silliness of “Cousin Cocaine” almost destroys the terror of “Sister Morphine,” that would be one of the real losses of our predicament, one we could hardly replace.

The amazing thing about this album is that this doesn’t happen. The confusion that manifests itself in a self-conscious tending of image, cuteness, hipster pretense, trickery and excess is fought off by the power Mick and Keith are able to derive from their way of dealing with the world as artists and it is ultimately dismissed by the music of the band. In spite of the moments when they seem to be trivializing their music it ought to be remembered that they don’t succeed. “Sister Morphine” stands as a chilling fragment out of our collective bad dream; the first part of “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” breaks free of its coy patter because Jagger is singing that nonsense in a great Little Richard squeal that ultimately has to triumph over whatever it is given to say, and because the song rocks through its few minutes of glory like few songs ever have. If they eventually blow the performance by jerking the listener, as if someone had punched a button from WROK to WJAZ, into a pleasant and pallid excursion into what reminds me more of the Ventures than anything else, then again, this is part of their confusion and their inability to know what to do with their music, their talent, and their own best impulses. The album does have its sewer, beginning with the move away from rock and roll in “Knocking,” scuttling through “Gotta Move,” bashing away at “Bitch,” and faking it through “I Got the Blues,” which sounds like a sop to the Stones’ very unimaginative horn men (“Whadda you guys play, anyway?” “Well, we do an outasight Mar-Keys imitation.” “Far-ooooot,” as Mick is reputed to put it, “You gotta hear me do Otis Redding.”) But then “Sister Morphine” wipes all that out and the album continues to the heights again.

“Moonlight Mile,” which is nothing more or less than our era’s “There Goes My Baby,” easily escapes its single flaw and builds into as fine a melodrama as Olivier ever played in; it sounds like a good theme song for his Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, as a matter of fact.

When the music is good on this album, as when the Stones are creating “Sway,” unbearably loud and with an accelerating intensity that really begs for the release that the strings finally bring, when they take the music away without really ending it (this song seems to fade up instead of out), then there is little that can interfere with the impact of the Rolling Stones. “Sway” is one of their finest performances, with a great title that made me think it was going to be a name-of-the-dance tune (you know, “come on do the Sway”); it may get lost like “The Singer Not the Song” or “She Said Yeah,” but only because it’s stuck between “Brown Sugar” and “Wild Horses,” which are so much easier to hear. But the halcyon noise of “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” the crash of “Brown Sugar,” Mick’s edgy vocal on “Sister Morphine” and his satisfaction in “Moonlight Mile,” they all break out of the shoddy context this album sets up for itself and which it pursues, virtually song by song, from beginning to end. If only “Sway” and “Dead Flowers” escape the basic conflict of the album, it’s because they walk the line so well, Mick skirting “black magic” to create an overwhelming sense of being trapped in the first and joking his way through the graveyard of an underground where flower power has turned into funeral wreathes and acid utopias into grimy needles in the second.

Some find this album decadent. I’d say rather that it tries to be decadent, it tries to obscure the variety and the vitality of what the Rolling Stones are, and fails. Its context is decadent; the title, the cover, perhaps the gut meaning of “Brown Sugar,” the flaunt of a title like “Bitch,” the doper cool. That, for certain, is a matter of taking one element of what the Stones are and what they have come to mean and attempting to pass it off, live it out or play it as if it was the whole story. But it isn’t the whole story and the music on the album is the proof of that. Their music is still much stronger than their confusion about what it is or what it is for, and that confusion, like the themes of the album itself, reflects events that both we and they share: Altamont, a plague of drugs, an isolation that has followed the weakening of a basically passive counter-culture, and a fragmenting audience for rock and roll.

Fragmenting or not, this has been the first album this year that one could hear without trying. It has been played constantly through FM tuners, screeched out of AM transistors and blasted out of windows until it is really public. Because of that it is not merely a history of the things that affect and afflict us—a “reflection of the times,” as condescending critics of rock and roll like to put it—it is part of that history. It deepens and intensifies what we already know, reminds us of things we might like to forget, allows us pleasure when nothing else will, and provides an excitement that matters to the way we get through the day and what we do with it. Because it is public—because while there are many who have not bothered with Joy of Cooking or J. Geils or Paul’s new one or whatever, there are few who have avoided the Stones even now—it re-creates a certain sense of common predicament and common values that we draw from few other sources. Because of that, the Stones are not only rhythmic historians but aesthetic politicians, and their album, while hardly political, is a kind of political event in our vague and aimless political community.

The possibilities of sex, drugs, frustration and satisfaction in Sticky Fingers and the rest of the Stones’ music are possibilities that some of us have rejected, some of us have chosen, that some of us are struggling with and wondering about. There is nothing monolithic about it. It is not the distance or the strangeness of the situations of Sticky Fingers that puts some people off and makes them call it decadent, but their closeness and their possibility. They may be playing dangerous games with risky material, but that is what artists are for, after all; they are not in business just to amuse the audience and pat them on the back like the divines behind Jesus Christ Superstar. Closing off certain options that have opened up on our streets is our job, not theirs. Their job is to emerge from the confusion and self-consciousness which mars this album and which would have destroyed it had there not been so much left. They have to come up with some tougher answers to the question of what it means to be the Rolling Stones instead of sliding on the most trivial elements of their past, elements we will eventually ignore if they don’t. When these options of smack and a sexual sneer are closed off the Stones will no longer be singing about them, because true to their name, they are not much for nostalgia, and they don’t look back.

Creem, October 1971