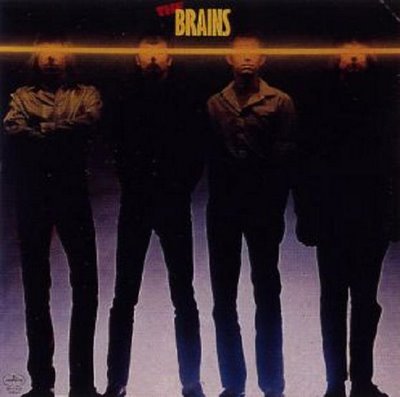

The Brains (Mercury). Last year, this unknown quartet from Atlanta broke hearts all over the country with a bitter, stoic homemade single called “Money Changes Everything.” Their debut album includes a fine new take of that song, but it’s a measure of their depth that they don’t even lead off the LP with it. Instead, they begin with an instrumental that suggests a slightly doomstruck rewrite of Duane Eddy’s “Because They’re Young” and follow it with nine tunes so full of neurotic detail, melodrama and acrid humor you might hear them as stories leader Tom Gray has hoarded against the day he’d have the nerve to tell them.

Combining jagged guitar, loud and sometimes madly syncopated drumming and Gray’s rich, evocative organ playing, the Brains attack their material with the heedless momentum of a bar band that’s spent years playing the Top 40, which is also how they look; they sound as if they recorded inside a large cardboard box, which is exactly how they ought to sound. Gray sings like a prophet, or a prisoner: Every one of his songs seems to be set in the middle of the night. Pinning down teenage doper-intellectuals, struggling with love or turning his back on it altogether (“Real life—you can have it,” he snaps in an inspired moment. “I’ll take the girl in the magazine”), Gray is singing about fear, and he is utterly convincing.

Young Marble Giants, Colossal Youth (Rough Trade import). The Giants—a woman on vocals, two men on bass, guitar and organ, and a machine on drums—got their start as one of eight bands to place tracks on an album compiled by a producer in their hometown of Cardiff, Wales: an album that resulted when said producer announced his intention to release a record made up of songs by the first eight bands to send him tapes. If anything, Colossal Youth sounds even more unlikely. Imagine one of the girl singers from the Fleetwoods (with twenty more years of knowledge in her still-creamy voice) backed by the minimalist offspring of Booker T and the MGs, and put them to work on fifteen slow, chilly tunes that effortlessly live up to titles like “Searching for Mr Right” or “Credit in the Straight World.” The end product is intelligent, provocative, disconcerting, but also, once you’re used to it, strangely calming. The group’s name, by the way, refers not to anything Welsh, but to a famous hoax perpetrated in 1869 in Cardiff, New York, when an enterprising tobacco farmer named George Hull decided to take advantage of the Bible’s claim that “there were giants in the earth” by putting one there.

The Fabulous Thunderbirds, What’s the Word (Chrysalis). From the Austin band best known for making the most boring album of 1979, a shock: a straight-ahead, no-apologies revitalization of that most entropic of rock ‘n’ roll styles, white rhythm and blues. “Runnin’ Shoes” (Howlin’ Wolf’s “Down in the Bottom” by way of Juke Boy Bonner) features a Jimmie Vaughan guitar riff so hypnotic there doesn’t seem to be another instrument on the track. Singer Kim Wilson doesn’t do much more than wail “Yay-eh” over and over, but he’ll have you trying to plumb the eternal mysteries in his tone: He makes that “Yay-eh” (generally translated as “yeah,” but perhaps best understood as a Texas-blues rendering of “Yahweh”) sound like the answer to every question. There are as well “The Crawl,” which is a name-of-the-dance number, and “You Ain’t Nothin’ But Fine,” the 457th investigation of the little-girl-let-me-walk-you-home theme—talk about eternal mysteries—both handled as if no one had ever thought of such things before. All this record lacks is a question mark at the end of its title.

The Feelies, Crazy Rhythms (Stiff import). Though they’ve made nothing like a perfect record—the singing is awful, which must be why there isn’t much of it, and the drumming is sometimes woefully out of time—it’s absurd that this neosurf-music band from New Jersey had to go to England to find someone willing to take a chance on it. No doubt, the Feelies are odd. Four young men who appear on their album jacket as refugees from the last Andy Hardy movie, their stripped-down guitar wizards’ rock ‘n’ roll is as pure and arty as the Brains’ is pure and bloody—and yet it’s also the kind of stuff that makes you grin almost before you’ve heard it, which the Brains’ music is not. The indelible tossed-off guitar breaks from a dozen Buddy Holly tunes, Ritchie Valens’s lead-in to “La Bamba,” Lou Reed’s taut repetitions in “Sister Ray”—the Feelies have absorbed them all, and in their hands such timeless fragments come out whole and startlingly modern. Pick to click: “Raised Eyebrows,” a seamless resolution of the kineticism of the Surfaris’ “Wipe Out” and the ethereal grace of the Chantays’ “Pipeline.”

Willie Nile (Arista). Working out of Greenwich Village, Nile is one of only two people in recent years to put flesh on the discarded skeleton of folk rock (the other is Robin Lane—see below). With a thin, reedy voice not far from that of Loudon Wainwright III, Nile may be a sucker for the vague weather-and-landscape imagery that causes so many folk-rock lyrics to evaporate somewhere between the glen and the fen, but he’s capable of blazing emotion, and he has the uncanny ability to sound as if he’s whispering secrets even when he’s screaming his lungs out. Recorded with unprecedented vibrancy by Roy Halee, the searing band Nile has put together for this debut recalls, at its best, the daring of the Dylan-Hawks combination of the mid-sixties—and its best comes with “Sing Me a Song,” the final cut. As Nile establishes a tension between a plea for carnal deliverance couched in apparently harmless metaphors (“Pretty babe—write me a poem”) and a melodic theme rooted in the menacing modal figures of an Appalachian ballad, electric guitarists Clay Barnes and Peter Hoffman take up the challenge, shaking the performance with a ferocity that rivals the twin-guitar rave-ups of Neil Young’s “Cowgirl in the Sand” and Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “That Smell.” There’s one thing wrong with “Sing Me a Song”: It ends.

Robin Lane & the Chartbusters (Warner Bros.). A Boston band led by a former Angeleno, the Chartbusters take their cues mostly from L.A. Echoes of the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and the Leaves—and of the early Stones, the Beatles and Detroit’s Spikedrivers, who gained some California airplay in 1967 with a biting folk-rock masterpiece called “Strange Mysterious Sounds”—are all over this album: heart-stabbing guitar duets and brittle rhythmic changes that seem to hit with far more force today than they did the first time around. The feeling the music gives off is that of unrelieved foreboding, backed up by passion blindly seeking an object—any object. Whether furious (“Without You”) or deliberate (“When Things Go Wrong“), Lane’s songs are desperate: scattered tales of picking up men, of trying to make contact with one who shrinks from her touch, of murder.

In her early thirties, bearing down with all she has on her first album, Robin Lane is a born-again Christian whose mission is not to save you from sin but to make life real. Goodness is not the issue here—nor, one might think, in Lane’s faith. Rather, the terror that motivates her music is rendered palpable; so is hope; so is hope abandoned. Strong as the Brains’ music is, Robin Lane’s music shows it up as the sound of young men who can’t wait to grow out of their fears. Such a premise isn’t a lie, nor is it as close to the truth as she gets.

In the last year or so, the United Kingdom has produced a handful of young, often biracial bands—most notably the Specials, Madness, the Selecter and the Beat, all of whom began or remain on the Specials’ co-op 2 Tone label—who have emerged from the ruins of punk to carry on the battle for social justice and good times with a new version of ska, the prereggae Jamaican dance music that was the beat of choice among the Mods of the early and mid-sixties. Across the water, 2 Tone (complete with revived Mod fashions, porkpie hats and a whole borrowed iconography of Cool) became an instant rage, and it has yet to show signs of cresting. Ska, word had it, was pure fun, “crazy” but not crazed, and its politics, if thinner than those of punk, were progressive enough: calls for interracial youth solidarity and intelligent use of contraceptives.

But the enormous commercial success of the ska revival in the U.K. (and its more limited but still substantial success in the U.S.A., which has taken to 2 Tone with a readiness withheld from English punk and any music from Jamaica itself) is suspicious, because on the evidence of the albums released by the Specials, Madness and the Selecter (the Beat have put out only three singles, and only in Britain), these groups are not very good. And that leads me to think that their popularity has less to do with the potency of their music than with the way that music is being used: as the means to a reactionary retreat from the punk insistence on Armageddon-as-daily-life, and as a flanking action against the imprecations of the postpunk avant-garde (Gang of Four, John Lydon’s Public Image, Essential Logic, Young Marble Giants and a score of others).

As Dick Hebdige details in Subculture: The Meaning of Style (Metheun), a first-rate new book on British music-based youth movements, white working-class kids in England have always taken their cues from contemporary black music; it is of more than minor significance that large numbers of white (and, in England, black) youth have found it necessary to excavate a style that has been static for more than a decade. Why, if not to evade the demonology of punk and the militance of present-day reggae?

Were they not the hottest band in the U.K., the Specials would be simply a curio: an earnest group of two blacks and five whites who play stiffly and have yet to think about what it would mean to get more than a bright, rote enthusiasm into their vocals. Almost every moment on The Specials (2 Tone/Chrysalis) is musically flat, emotionally barren. The lilt in the horns, the personality in every inflection on Dandy’s 1967 Jamaican original of “Rudy a Message to You,” now a Specials trademark, are completely absent; you can hear the Specials reaching for those effects—as effects.

The Selecter, a racially mixed band with a woman as lead singer, is somewhat better: Too Much Pressure (2 Tone/ Chrysalis) at least chases its title. Madness, an all-white group, is very much worse: It is to ska what the Blues Brothers are to R&B. They deal with their estrangement from the music of a black culture by celebrating the distance provided by the color of their skin.

One Step Beyond… (Sire) is a racist album: Madness has turned ska into a minstrel show, reducing the style to its foolishness. But that foolishness was the result of the anarchic commercial context of early Jamaican pop, in which anything could be tried at least once—a foolishness that led to an unfettered experimentalism. It reached its height in the work of Prince Buster, from whose classic “Madness” the new ska clowns have taken their name.

Prince Buster was a joker, but he was also a visionary. His triumph came with the astonishing “Judge Dread” trilogy, a set of three-minute comedic morality plays in which a black judge sentences a gang of Kingston rude boys to hundreds of years in prison, jails their attorney for life when he has the temerity to appeal, and then, having reduced all wrongdoers to tears, sets everyone free and steps down from the bench to dance in the courtroom (see The Fabulous Sound of Prince Buster, Fab import). With “Madness” he offered a parable about the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed, a subversive affirmation of the consciousness necessary to break that relationship. To the man in power, Prince Buster was saying, I appear mad because that is the only way the oppressor can deal with the fact that “someone is using his brain.” His true inheritors are the Rastafarians, believers in the divinity of Haile Selassie and redemption in Africa, both manifestly “mad” tenets of a religion and a way of life that allows for independence and identity within “Babylon”; for Prince Buster, “Madness, madness—I call it gladness” was the cry of a free man. For the group that has captured his song, it’s just a laugh.

As for the Beat, a 50-year-old Jamaican saxophone player fronted by black and white Birmingham punks who owe more to Toots and the Maytals than anyone else, their pumping, scarifying “Twist & Crawl” (Go-Feet import)—which is not a name-of-the-dance number—is one of the most exciting singles I’ve heard this year.

Real Life Rock Top Ten

- Gang of Four, Entertainment (Warner Bros.)

- Michael Thelwell, The Harder They Come, a novel (Grove Press paperback)

- Eric Clapton, Just One Night (RSO)

- Bob Seger & the Silver Bullet Band, “Betty Lou’s Gettin’ Out Tonight,” from Against the Wind (Capitol)

- Public Image Ltd., Second Edition (Island)

- Vapors, “Turning Japanese” (UA import)

- Toots and the Maytals, Just Like That (Island)

- Aaron Neville, “I Love Her Too,” from the soundtrack to Heart Beat (Capitol)

- Robert Nighthawk and His Flames of Rhythm, Live on Maxwell Street—1964 (Rounder)

- Pete Frame, Rock Family Trees (Music Sales paperback)

New West, August 1980