The Clapton cover promised an uncredited “The Rolling Stone Interview: Eric Clapton.” Immediately following the three-page interview was an installment of the column by staff critic Jon Landau, which ran in nearly every issue, on Cream.

Landau had developed a thoughtful, detailed, musicianly style of writing that radiated consideration and fairness. More than that, his work contained a somehow unassailable authority—and in this piece Landau took up the question of the instantly celebrated trio Clapton had formed with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker. “Clapton,” Landau wrote, “is the master of the blues clichés of all the post-World War II blues guitarists.” According to stories that once were fact and are now legend—there is today, thirty-eight years later, a lengthy, bizarrely researched web site devoted to this single column—when Clapton read what Landau wrote, he fainted. And what was his label going to do? On the page facing Landau’s was a full-page Atco Records advertisement for the first two Cream albums. The footnotes barely matter: RS 14, July 20th, 1968, a headline for a Frank Zappa cover, “Cream’s New Record Bombed,” with most of the magazine’s front page devoted to a picture of Jack Bruce playing cello during studio sessions for Wheels of Fire, the Cream album in question, and then Jann Wenner’s lead record review, which began, “Cream is good at a number of things; unfortunately songwriting and recording are not among them,” and which ended with an attack on the album’s cover art and a final sentence: “The album will be a monster.” It was, but well after the headline that ran in the next issue: “Eric Clapton Announces Cream Split.”RS 10 was shocking then and it’s shocking now: a publication that, from the perspective of someone picking up a copy to read about Eric Clapton, did not seem to even consider the question of censoring its writers—in other words, itself—in order to protect what was then its only reliable source of revenue; a publication willing to bite the hand that feeds it. What that suggested was what really fed Rolling Stone at that moment was its readers, or their specter: the notion that what one wrote was being read, talked about, argued over, praised and damned. I was one of many who waited eagerly for each new issue. Early on, Rolling Stone carried a little ad soliciting writers (“HELP!!… Send us something we might like to print… Maybe well print it; maybe well pay you”); in the span of issues I’m looking at now, I became one, then an editor, then again a newsstand buyer. From the first, it was uncanny, unexpected, what you’d been waiting for without knowing it: a music magazine that didn’t insult your intelligence, as even the radio-oriented Hit Parader did, as even Crawdaddy!, a self-consciously intellectual journal that well predated Rolling Stone, did in its own insider’s way. This was plain talk, but with oceans of implication behind it.

At the start, Rolling Stone didn’t have a real cover. It was a fold-over tabloid; until RS 9, April 6th, 1968, “the cover” was simply what illustration and headline appeared above the fold. For RS 1, November 9th, 1967, there was a still of John Lennon from the film How I Won the War. The only striking visual in the whole of the twenty-four pages was a double-page Buddah Records advertisement for the debut album by Captain Beefheart, Safe as Milk, and it was stunning. Rolling Stone began with what now seems an overwhelming field for page art: Until RS 142, August 30th, 1973, pages measured eleven-and-three-quarter inches by sixteen-and-a-half. The Safe as Milk ad was simple: a baby with an enormous, perhaps five-times-life-size Humpty Dumpty head and unnervingly knowing eyes, as if this was Captain Beefheart; in 1967, few knew any better. As you page through the first year’s worth of Rolling Stone, the ad’s image rules; nothing comes close to it. In RS 22, November 23rd, 1968, it won the Best in Show award for excellence in advertising. One of the judges was Robert Kingsbury, who had become the Rolling Stone art director with RS 16, August 24th, 1968.Before Kingsbury, Rolling Stone covers—above-the-fold or the real thing—were conventional: head shots or performance shots. Tina Turner dancing for RS 2. For RS 4, three onstage pictures in a row: Donovan, for an anti-drug statement; Jimi Hendrix, for old tapes disguised as a new album; Otis Redding, for his death. There was no sense that the news an illustration was meant to highlight might shape the choice of the illustration; what was used was what was available, cheap or serviceable.

There was little sense even of how to use what the magazine was creating. Staff photographer Baron Wolman had an unmatched feel for the moment when a performer sucked the flattery of a camera into himself or herself, and so got people to come out of themselves, to drop their modesty and anonymity, but often Wolman’s touch was nearly wasted. RS 6, February 24th, 1968, included one of Wolman’s finest pictures, a lordly B.B. King with cigarillo reduced to one-sixth of a page. (It would be used again, with much greater effect, for Landau’s column five issues later.) RS 7, March 9th, 1968, featured a two-page Hendrix interview with eight Wolman photos. Amid six performance shots, there was one that would become iconic, but here was pushed to the left side of a jumble of pictures: Hendrix speaking, not making grimacing performance faces, clearly thinking, taking time between words. The portrait would be rescued for the cover of RS 26, February 1st, 1969, and after that it spoke for Hendrix just as he spoke in it.

At first the magazine was more distinguished by its words than its pictures, as with Dylan sideman Al Kooper’s review of the Band’s Music From Big Pink in RS 15, August l0th, 1968—placed last in the record review section, and epochal: “This album was recorded in approximately two weeks. There are people who will work their lives away in vain and not touch it.” As a reader, I felt those words like a clap of thunder; they went into my memory as I read them, and nearly forty years later I can quote them word for word. But aside from a head-to-toe Wolman picture of Johnny Cash, running most of the length of a page—catching Cash’s dignity and command as he tilted his guitar into the air—there was little to look at that matched what Kooper and others were writing.

Robert Kingsbury was a droll, dour man, trained as a sculptor, older than most of the people at the magazine. He had the driest sense of humor imaginable—you had the feeling he got a joke before the person telling it did—and absolute confidence in his own judgment. The first cover under his stewardship was, in a way, the first true Rolling Stone cover: Elliott Landy’s soon-to-be-famous photo of the members of the Band spilling off a small wooden bench. There was a lake and winter trees in front of them; Landy was shooting from behind, which is to say there were no faces. You couldn’t tell who was who, and the drama of the picture and Kingsbury’s presentation—almost no type, straight black-and-white with a green border—made you want to know. “The Band”—the cover said these people could be anybody, from anywhere. It merely happened to be here, and them.

Under Kingsbury’s eye, Rolling Stone began to jump in a new way. For the cover of RS 18, October 12th, 1968, he picked the most stark of many performance photos Jann Wenner had taken for a long interview with Pete Townshend: Townshend with his arm raised for his windmill, in a half-circle of light, the black shadow of his body just to the right, a second Halloween self, and, at the foot of stage right, the silhouette of a man with glasses, gazing up. The singularity of the photo was in the way it placed the performer and the spectator on the same plane, as if only one could complete the other. Townshend’s last words in Wenner’s interview completed the photo: “When you are listening to a rock & roll song the way you listen to ‘Jumping Jack Flash,’ or something similar, that’s the way you should really spend your whole life. That’s how you should be all the time: just grooving to something simple, something basically good, something effective and something not too big. That’s what life is. Rock & roll is one of the keys of the many, many keys to a very complex life. Don’t get fucked up with all the many keys. Groove to rock &roll and then you’ll probably find one of the best keys of all.”

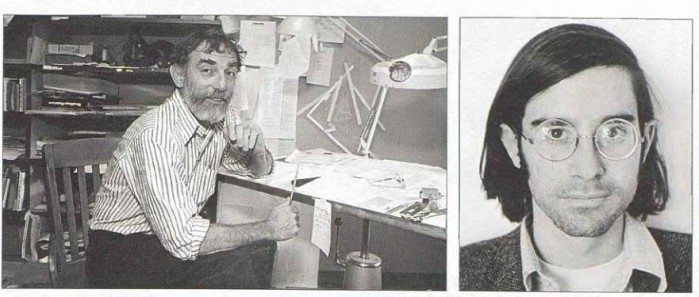

Robert Kingsbury, Greil Marcus

Kingsbury realized what the expanses of space in a Rolling Stone page were for. For a review of Hunter Davies’ authorized Beatles biography in RS 20, he used a full page for an odd photo of Paul, George and Ringo huddled over an apparently dead John. Cut down as an illustration, it would have said nothing; as it was, it was a kind of counterbiography, in a single image. Still folded over, the covers were only half the size of a page; as opposed to how Landy shot the Band portrait, where the background was in essence the foreground, Kingsbury began to favor a photo trimmed out of its background, then placed against a field of white. This allowed for a lot of type on the cover, but it took the drama out of the cover art.

For RS 22, November 23rd, 1968, it didn’t matter. This was the “Two Virgins” cover. John Lennon and Yoko Ono nude, from the back, looking at you over their shoulders; inside, they faced the camera. A street vendor in San Francisco was arrested; a postmaster in New Jersey, through whom all Eastern subscription copies were routed, refused to mail them. The Boston distributor refused to distribute it. The cover was quiet again for RS 27, February 15th, 1969. For a long story on groupies—opening up a world of sex, narcissism and submission most readers had no clue about—Kingsbury chose perhaps the least lascivious or simply provocative of the many portraits of groupie women inside. It was odd; the magazine was not visually exploiting its own story. Today, where every angle is played for all it’s worth, this seems very nearly self-destructive: What were they thinking? Kingsbury was thinking: This is precisely the only image I have that won’t exploit the story.

The unexpected was the currency. For RS 31, Apnl 1969, there was a cover featuring Sun Ra, his eyes covered by opaque sunglasses tinted yellow. You couldn’t read the picture, and you couldn’t really read the headlines on the cover: “Earthquake Corning!” “Miami in Ruins!” “And a Cast of Dozens.” For Miami or the earthquake? A single picture that took up five-sixths of two pages was even more opaque: a shadowy, spooky Gered Mankowitz photo of the four members of Traffic sitting on the floor in a tiny room. There were two pages on a Peace Garden created by the eighty-eight-year-old San Francisco artist and pamphleteer Peter M. Bond, a.k.a. Pemabo, a junkyard of signs proclaiming warnings and hope, among them “Make Peace Now Got to Hell Later” and “Luther Reformed and Pemabo Clarifies”—a spread so intense you wished the pages were bigger. RS 33 included a report by Ralph J. Gleason on the debut of the Band in San Francisco, keyed by a portrait of organist Garth Hudson, in profile against a black background, that took up more than half the page. Hudson was onstage, in performance; he seemed abstracted from any, ordinary activity, not playing, not moving, but contemplating the future and the past.

Kingsbury played around. For RS 38, he put an uninteresting picture of Jim Morrison on the cover; inside, as the lead for a long interview by Jerry Hopkins, he placed a dark, deep, full-page photo, making Morrison’s head greater than life-size, and all you could really see was his heavy beard, his closed eyes, his thick graying hair. In the aftermath of his felony arrest at a Miami Doors concert for “Lewd and Lascivious Behavior in Public by Exposing His Private Parts and Simulating Masturbation and Oral Copulation,” which led to canceled shows and put the band’s future in question, Morrison looked like a Vietnam veteran who’d been living on the streets; compared to various photos of Morrison from earlier days scattered across the interview pages, this was a bomb. In the Records section, for a two-page review of the Bonzo Dog Band’s Urban Spaceman that included a full-length shot of Bonzo Neil Innes, Kingsbury built his right leg out of type, effectively allowing the comment on the group to nibble the singer to pieces. There were two early, paired reviews by Lester Bangs. Bangs tattooed LOVE on the knuckles of one of his hands for Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band’s Trout Mask Replica (“What the critics failed to see was that this was a band with a vision”). He tattooed HATE on the knuckles of the other for It’s a Beautiful Day, the debut album by the band of the same name (“In conclusion: I hate this album. I hate it not only because I wasted my money, on it, but for what it represents: an utterly phony, arty approach to music that we will not soon escape).

The Woodstock issue—RS 42,September 20th, 1969—was not memorable for its art. As opposed to the “Disaster in Woodstock” coverage in daily newspapers, Jan Hodenfield’s sometimes profound article “It Was Like Balling for the first Time” said what happened: a combination car crash and celebration.

It was almost a portent, the cover of RS 49, carrying the date December 27th, 1969, but appearing on the stands in November: a quiet, blank, contemplative portrait of Mick Jagger by Wolman, tinted in pink. It seemed like a portent as one looked at it then, not in hindsight: Jagger was gazing into what was to come, whatever it was, as if it had already happened. Weird, but you forgot about it, especially given the cover line: “The Stones’ Grand Finale.” Or the headline on the front page: “Free Rolling Stones: It’s Going to Happen.”

The Altamont issue followed. The image on the cover, by Michael Maggia of Photographies West, was suspended, just as the portrait of Jagger was, except here you saw people waiting, with no sense at all that anything was going to come. There were people sitting and standing in a half-light, the first morning sun rays cutting out of the mist, people looking away from one another, as if they were not all of them actually in the same place at the same time. Again, it was a refusal to sensationalize: Inside there were pictures of Hell’s Angels beating people in the crowd with pool cues, pictures of violence so stylized and dramatic they looked less like event photos than movie stills. The long, long story—edited principally by managing editor John Burks, out of contributions from a score or more of writers—began with Burks’ interview with an eyewitness to the Angels’ murder of fan Meredith Hunter of Berkeley, describing how Hunter pulled a concealed pistol only after being attacked, chased from the lip of the stage, and then stabbed for the first time. Before that grand finale, the Rolling Stone editors who were there toyed with the idea of refusing to take the bait of the day, which was ugly and mean from the start. Why not bury the event in the bottom left corner of an inside page: “Stones Play Concert”? At a meeting a few days later, Jann set the story: “We are going to cover this from top to bottom. And we are going to lay the blame.” What we ran satisfied no one at Rolling Stone, but it fixed the meaning of the event for all time everywhere.

RS 60 was “On America 1970: ‘A Pitiful, Helpless Giant'”—President Nixon’s words for what America would be without his will to do what had to be done. The issue was put together in a panicky thrill over the explosion of protest on campuses and in city streets all over the nation after Nixon took the Vietnam War into Cambodia: story after story, on the four white students shot by National Guard troops at Kent State in Ohio but also on the almost instantly forgotten police killings—“1,000 Rounds in 7 Seconds,” read the Rolling Stone headline—of two black students in Jackson, Mississippi. More powerfully, there was a coolly detached, disgustedly ironic hometown dispatch on the police murders of six young black men in Augusta, Georgia, built around Bill Winn’s long quotations from the coroner’s reports, which to Winn read like Faulkner or O’Connor, a reminder of the strain of American violence that was both part of the moment and outside of it. And there was a chilling report on Nixon’s 4 A.M. visit to the Lincoln Memorial to talk with some of the students who, having poured into the capital for a giant protest rally, were spending the night on the huge memorial steps. “For the first time in ages,” staff writer John Morthland said, “the President of the United States was standing around talking to common, everyday people.” “He was talking to the floor, not looking up,” one person told Morthland. “Nothing he was saying was coherent… he was mumbling at his feet.” The story took up almost the whole issue; in these pages you could hear the nation talking to itself.

Then the country darkened; there’s no other way to say it. The words are corny—no one had any better words for what was happening. In that mood, the deaths of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin the following fall almost did not come as surprises. The cover for Hendrix, RS 68, October 15th, 1970—a face with a full, bubbling background and heavy type for his name and his dates—set the mold for the many death covers to come; despite the malaise that preceded Hendrix’s death, no one expected that “to come” would mean the next issue. When, following the Janis cover, Grace Slick appeared on the cover of RS 70, November 12th, 1970, the format of a head and a dark background was precisely the same, and even given the absence of “1939-1970” it was hard not to see the issue and think that it was saying that she, too, was dead.

It was fitting that this cycle of Rolling Stone came to an end with a cover that at once matched these awful landmarks and broke with them. Annie Leibovitz’s picture of John Lennon for Jann Wenner’s interview, in RS 74, January 21st, 1971, was placed as Hendrix, Joplin and Slick had been, a close shot of a face. But it was the first cover in a while that you couldn’t register in a glance. As the first part of a very long look back that would appear in book form as Lennon Remembers, with the same cover, Leibovitz’s portrait implied less “Now It Can Be Told” than that only now, as if the previous decade had been an amnesia, could Lennon remember where he had been and what he had done. Leibovitz had Lennon looking slightly to the left, his eyes clear, full of years of “Wish I didn’t know now what I didn’t know then” and ready for the future.

None of the other Leibowitz photos used in the interview had the suggestiveness of the cover picture, or the care in framing, which is to say its stopping the moment, making a pause, promising not the talk the cover is in fact promising, but silence, as if what “Lennon Remembers” really means is, yes, I remember, but I’m not telling. He looked great—as always, he looked like someone you’d like to meet. And in the pages behind the cover, you did.

Rolling Stone, May 18, 2006 (Issue #1,000)

Interesting piece by Marcus on Rolling Stone’s early days. I didn’t start reading RS until 1969, so I missed some of the primordial details Greil mentions, though I’d read somewhere years later that Eric Clapton allegedly passed out after reading Jon Landau’s attack on his qualities as a bluesman. It’s fascinating to me now to learn that Landau’s review ran right across from an ad for Cream’s first two albums, from Atlantic Records’ Atco label, and that Jann Wenner himself backed up Landau’s findings editorially when Cream’s “Wheels of Fire” album came out a bit later. Fascinating and most ironic, because in later years, two rock critics of my acquaintance were dismissed from writing for Rolling Stone by Wenner after they’d filed negative reviews: Lester Bangs for dissing a Canned Heat album in 1973, and Jim DeRogatis for doing the same to a Hootie & the Blowfish disc (latter-day Atlantic product) in 1996. In both instances, Wenner was apparently more interested in keeping the advertisers happy than in getting the critical lowdown on the albums.

A rough Atlantic crossing here, as Atlantic Records (at least the classic Atlantic of the 1960’s) remains my favorite label of all time, though I certainly didn’t care for Ahmet Ertegun’s increasing disregard of his own aesthetic standards from the 1970’s on. If *I* ran Atlantic [probably right into the ground — Ed.] a number of acts never would have been signed to it in the first place, no Yes, no Firefall, Genesis, Phil Collins, nor Hootie & the Blowfish, among others. Jim likely had that one right, Jann, though I’m glad to know now that you could still trust and honor your writers’ opinions during that tumultuous year of 1968.

Incidentally, while I’m on this topic, recently I’ve seen claims on at least a couple internet sites (including Wikipedia) about Lester that he became an editor at Creem after getting bounced from Rolling Stone. Not so, no cause & effect involved there: Lester moved to Michigan to take the Creem job in the fall of 1971, but continued to freelance for numerous other magazines, including Rolling Stone, while editing and writing for Creem. He lost the RS gig in 1973, as noted, but Paul Nelson brought him back to RS as a record reviewer in 1978.

Pingback: Rolling Stone | 1960s: Days of Rage