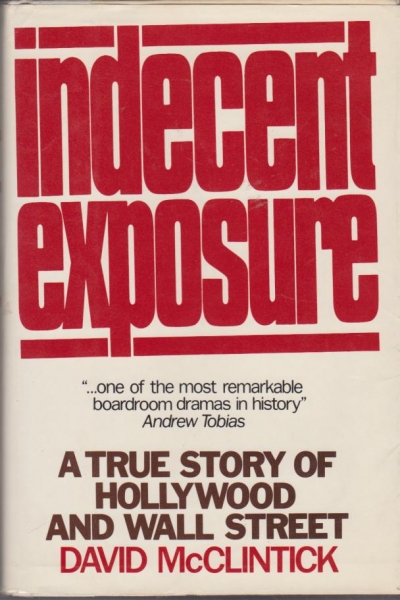

Indecent Exposure: A True Story of Hollywood and Wall Street, by David McClintick (Morrow, 544 pages, illustrated, $17.50)

It’s easy to get carried away after reading McClintick’s book, which is primarily a behind-closed-doors reconstruction of the power struggle between Hirschfield, who wanted Begelman out, and Allen, who wanted him in. What is most impressive about this struggle is its triviality, its stupidity, its mendaciousness, its meaninglessness: a King Kong-style clash of dinosaurs in the middle of an ordinary game of Hollywood musical chairs: Huff, puff! Hirschfield is down, bleeding from a dozen wounds! Rosenhaus plants his foot on Hirschfield’s chest and beats his breast! Then Rosenhaus croaks and Hirschfield goes off to run another studio.

McClintick is sober throughout his presentation, even if you can occasionally sense him wanting to cut loose with a twelve-point scream: “CAN THIS BE HAPPENING?” (Groucho slides across the boardroom table, proffering cigars, eyebrows bouncing, hopping from one chair to another in instantaneous multiple disguises…) Take the moment in late 1977 when the board finally gave in to Hirschfield’s argument that as a company officer Begelman had to go. No way around it: the directors were mad for the admitted four-time embezzler and forger, but Columbia was a public company, subject to the Securities and Exchange Commission. (To make Begelman “whole and happy” financially, they’d give him a lucrative “production and consultancy deal,” and, if Rosenhaus had had his way, would have taken out full-page ads in the movie trades puffing the thief as the savior of the company.) So Begelman was finally, if temporarily, out, and the board moved on to a discussion of a TV production arrangement:

Matty Rosenhaus insisted that David Begelman’s approval be sought before the board voted.

“But Matty,” Hirschfield said… “David’s no longer with the company.”

“Well, he’s a consultant, isn’t he?” Rosenhaus said. ” …In his capacity as a consultant, he should approve deals like this.”

“Matty, David has nothing to do with this deal,” Hirschfield said. “You’re not going to be able to run to David every time you want to approve a movie or television project.”

“But that’s what consultants are for,” Rosenhaus insisted. “He’s supposed to approve these projects.”

“Matty’s right,” Herbert said. “That’s a great suggestion. That’s what we’ve got David as a consultant for. We’ll really get our money’s worth.”

Leo Jaffe was instructed to go to his office and telephone Begelman in Los Angeles. Begelman blessed the TV deal.

So much for texts on corporate economics, or, for that matter, the dictionary’s definition of “consultant.” Whether Begelman was in or out, the board was going to make sure he ran the studio. Faced with this pressure—and near blackmail—Hirschfield reinstated Begelman; then Jeanie Kasindorf’s New West exposé of Begelman’s alleged 1960s mismanagement of Judy Garland’s affairs blew him out of the water. Begelman resigned—and, with the board behind him, nailed Hirschfield for a production deal that included a yearly income of $500,000 (far more than he had made as a Columbia officer), office space, staff, car, $25,000 in insurance premiums, $26,000 for entertainment, first-class travel plus $1,500 a week in expenses while on trips, legal fees, and production credit above the title of his pictures. Predictably, relations between Hirschfield and the board deteriorated after this settlement, which in effect rewarded Begelman for his crimes. Finally, Hirschfield presented the Columbia board with a letter detailing its interference with his job as chief executive of the company. The board almost fired him—but backed down (he was fired two weeks later). After the meeting, Hirschfield—whose naiveté was as great as all outdoors—found himself alone with Matty Rosenhaus, a man whose life had been warped by the fact that he was not visibly a two-year old, but who did his best to impersonate one.

“You’re a liar! A liar! A liar!” [Rosenhaus] screamed at Hirschfield, his face flushed, spittle spewing from his mouth…. “Liar! Liar!”

You can almost feel David McClintick thinking: “Is there any way I can stick in ‘Pants on fire!’ and get away with it?”

There’s much more—for example, the way the Hollywood press (Rona Barrett, assiduously cultivated by Begelman, but also the L.A. Times‘s Charles Champlin) rallied to Begelman’s defense, not with facts but with anti-Hirschfield innuendo. McClintick has the rare talent for making a complicated story easy to follow: through all the machinations, you never have to remind yourself as to the identity and loyalty of “Allen,” “Jaffe,” “Stark,” and so on. Still, the book does not add up.

Though by no means only an as-told-to number, Indecent Exposure is essentially Alan Hirschfield’s story: he is McClintick’s primary source, and he is the character in the Begelman melodrama the reader comes to know best. The problem is not simply that the reader is inevitably led to sympathize with Hirschfield, as opposed to Allen, Rosenhaus, et al (Hirschfield is not presented as a fool, but McClintick is too honest a reporter to keep from exposing him as one); the problem is that, for the most part, the reader is given access only to Hirschfield’s motives, doubts, and private rages.

Thus in Indecent Exposure Alan Hirschfield is a well-meaning man who struggles with forces that he cannot understand—forces the reader cannot understand either. Allen, Rosenhaus, Stark, and Begelman himself are phantoms, manifestations of irrationality—inexplicable. What is the source of Ray Stark’s power over Columbia Pictures’ board of directors? After 544 pages, I don’t know. Why was David Begelman treated by men like Herbert Allen and Matty Rosenhaus as if he were a god? I can’t tell you. In a Hollywood novel, the Begelman figure would exercise bizarre sexual (or, at the very least, financial) power over his corporate supporters; McClintick makes no suggestion of any such thing. We follow Alan Hirschfield home after a board meeting, but very rarely Herbert Allen or Ray Stark (who had received reports over the phone)—or David Begelman. The story is out of sync.

One cannot, of course, blame McClintick for failing to record the testimony of people who had good reason not to speak to him, who had much to hide. The point is to judge a book given its resources, and on analytical grounds this book falls short.

What, one has to ask, was the source of Begelman’s control of (or, what were the essentials of his seduction of) men of independent wealth and clout? The resurgence of Columbia Pictures is not a sufficient answer; McClintick’s account makes clear that the attachments of Allen, Rosenhaus, and others were not based on any balance sheet. Why did the board contain the facts of Begelman’s crimes? Begelman was “suspended” pending an account of possible “improper financial transactions,” which everyone in Hollywood and on Wall Street understood to mean “padding his expense account”—mere he-got-caught compared to his felonies. And how was the board able to shield Begelman from the media for three months? Why did the plain facts of Begelman’s moral incompetence not for a moment deter the majority of the Columbia board from its full support of an admitted forger?

We don’t know what Stark, Allen, Rosenhaus, or Begelman thought of any of this—not, at least, from McClintick’s account. But there is a suggestion. McClintick, not Jewish, notes more than once that almost all of the principals in his story, Hirschfield included, are Jews. Could it be that, like the Sicilians in The Godfather, these Jewish Americans perceived themselves as distrusted and embattled within a greater America, and thus distrusted American justice, and thus felt it necessary to take care of their own—to protect David Begelman from the impersonality of WASP justice and, worse, WASP judgment? (Again and again, WASP corporate and banking executives tell Alan Hirschfield that anyone who’d done what Begelman did would have been bounced from their companies in a minute—if you believe that, and McClintick seems to, then the Easter Bunny lives.)

There is no ethical framework to the David Begelman story: that is the inescapable burden of McClintick’s book. Participants perceived the matter as a power struggle (Hirschfield, would-be producer, versus Begelman, studio head) or as a psychological problem: Poor David! Let’s give him money so he feels better, so he’s whole! As to what was right, only Cliff Robertson, who blew the whistle after discovering a Begelman-forged check, comes out clean, a paragon of WASP rectitude who, though he never bothered to press charges, got a four-year Hollywood blacklisting for his trouble.

David McClintick’s book is not definitive. It is not brilliant. It is entertaining and it is disturbing. Read it for what it is, and question it as you read.

Caveat Emptor

Courtyard Housing in Los Angeles, by Stefanos Polyzoides, Roger Sherwood, and James Tice; photography by Julius Shulman (University of California Press, 219 pages, $24.95). This is an unfortunate book, because the subject is so good and the execution so poor. The scholarly and readable texts can’t really be faulted, but the black and white photographic reproduction is so dull and hazy it’s almost impossible to see what the writers are talking about. Or could it be that the quality of the pictures is a secret protest against L.A. air quality?

Bech Is Back, by John Updike (Knopf, 224 pages, $12.95). Not to put too fine a point on last month’s condemnation of the free ride that readers and reviewers give famous authors who produce third-rate sequels to second-rate originals, but this is too much. Seemingly flushed with the nearly unanimous acclaim he received for his second follow-up to Rabbit, Run, Updike has now produced a follow-up to his 1970 Bech: A Book. Being as it is the tale of a Jewish writer who finds fame, Bech Is Back rather bizarrely echoes last year’s Philip Roth sequel, Zuckerman Unbound, in which another Jewish writer found fame. The most fatuous moment of this utterly pointless exercise comes when Updike makes up quotes for real-life reviewers to ladle onto Bech’s bestseller. “‘An occasion,’ proposed George Steiner in The New Yorker, ‘to marvel once again that not since the Periclean Greeks has there been a configuration of intellectual aptitude, spiritual breadth, and radical intuitional venturesomeness to rival that effulgence of…'” Steiner ought to sue; he’s not capable of anything so clumsy, so aggressively empty. On the other hand, maybe Bech is Back does have a purpose. It’s so bad it makes even an Updike trifle like Marry Me seem accomplished.

California, October 1982

my grandfather was Matty Rosenhaus… now I know where I get my temper from!