I had seen the naked woman perhaps a dozen times during the day. Repeatedly she would choose a male, run toward him, throw her arms around his neck, and rub her body up and down his. The comeback was predictable: “Hey, baby, wanna fuck?” At this, the woman would commence a series of psychotic screams and run blindly into the crowd. After a few minutes she would calm down sufficiently to begin the game all over again. Eventually people began to keep their distance.

But now, in the dark, behind the stage, with only a little yellow light filtering through to where I was standing, waiting for the Stones to begin their first tune, the woman looked different. As she passed by, her head on her chest, I realized her body was covered with dried blood. Her face was almost black with it. Someone had given her a blanket to cover herself with—it was very cold by now—but she didn’t wear it. She held on to a corner, as if she’d simply forgotten to throw it away, and it trailed behind her as she walked.

Then I saw the fat man. Hours before—it seemed like days—he had leaped to his feet to dance naked to Santana as they kicked off the day. All good times, let it loose, don’t hang me up, uh-huh. The huge man seemed full of the Woodstock spirit, but those sitting near the stage, as I was, noticed that in fact he used the excuse of his dance to stomp and trample the people around him, particularly several young blacks. After a short time the Hell’s Angels, who had been placed in charge of crowd and stage “security,” got sick of the sight of him; they came off the stage swinging weighted pool cues and beat the fat man to the ground. He didn’t seem to understand what was happening; again and again, he got up and continued his dance-stomp. Ultimately the Angels got him out of the area and took him behind the stage, where they could continue their work with greater efficiency.

Like the naked woman, the fat man was now brown with blood. His teeth had been knocked out, and his mouth still bled. He wandered across the enclosure, waiting, like me, for the music. As the Stones began, the mood tensed and the gloomy light took on a lurid cast. The stage was jammed with sound people, Angels, writers, hangers-on. There wasn’t an extra square foot. Kids began to climb the enormous sound trucks that ringed the back of the stage, and men threw them off. Some fell ten and fifteen feet to the ground; others landed on other trucks. I climbed to the top of a VW bus, where I had a slight view of the band. Several other people clambered up with me, waving tape recorder mikes in the hopes of capturing the sound. Every few minutes, it seemed, the music was broken up by waves of terrified screams from the crowd: wild ululations that went on for thirty, forty seconds at a time. We couldn’t see the screamers, but with their sound, the packed mass on the stage would cringe backward, shoving the last line of people off the stage and onto the ground. As the fallen climbed back, small fights would break out.

As the Stones began, the mood tensed and the gloomy light took on a lurid cast. The stage was jammed with sound people, Angels, writers, hangers-on. There wasn’t an extra square foot. Kids began to climb the enormous sound trucks that ringed the back of the stage, and men threw them off. Some fell ten and fifteen feet to the ground; others landed on other trucks. I climbed to the top of a VW bus, where I had a slight view of the band. Several other people clambered up with me, waving tape recorder mikes in the hopes of capturing the sound. Every few minutes, it seemed, the music was broken up by waves of terrified screams from the crowd: wild ululations that went on for thirty, forty seconds at a time. We couldn’t see the screamers, but with their sound, the packed mass on the stage would cringe backward, shoving the last line of people off the stage and onto the ground. As the fallen climbed back, small fights would break out.

By this time it was impossible even to guess what the screams meant. All day long people had speculated on who would be killed, on when the killing would take place. There were few doubts that the Angels would do the job. A certain inevitability had settled over the event. The crowd had been ugly, selfish, territorialist, throughout the day. People held their space. They made no room for anyone. Periodically the Angels had attacked the crowd or the musicians. It was a gray day, and the California hills were bare, cold and dead. A full beer bottle had been thrown into the crowd, striking a woman on the head, nearly killing her. Fantasies of the 300,000 turning back toward Berkeley to take People’s Park back from the fence that surrounded it shifted by midafternoon to fantasies of the War Machine eliminating 300,000 enemies with nerve gas as they sat immobilized by the prospect of the Rolling Stones.

Behind the stage I could hear Keith Richard cut off the music and berate the Angels. I heard an Angel seize the mike from Keith. The screams were almost constant by this time. People on the stage were rushing forward now, then scurrying back. Two more kids made it onto the top of the VW, and it collapsed. They went right through the roof. Some of those who fell off proceeded to punch out the windows. With all this, the music somehow picked up force. It was very strong. I turned my back on the stage and began to walk the half-mile or so to my car. Heading up the hill in the darkness, I tripped and fell head-first into the dirt, and for some reason I felt no need to get up. I lay there, intrigued by the blackness and by the sound of feet passing by me on either side and by the sound the Stones were making. I began to abstract the music from the events that surrounded it, that were by now part of it. The Stones were playing “Gimme Shelter.” I tried to remember when I’d heard anything so powerful. I reveled in the song, and when it was over, I got up and went on to my car to wait for the friends from whom I’d been separated hours before, when the Angels first jumped off the stage and into our laps.

With all this, the music somehow picked up force. It was very strong. I turned my back on the stage and began to walk the half-mile or so to my car. Heading up the hill in the darkness, I tripped and fell head-first into the dirt, and for some reason I felt no need to get up. I lay there, intrigued by the blackness and by the sound of feet passing by me on either side and by the sound the Stones were making. I began to abstract the music from the events that surrounded it, that were by now part of it. The Stones were playing “Gimme Shelter.” I tried to remember when I’d heard anything so powerful. I reveled in the song, and when it was over, I got up and went on to my car to wait for the friends from whom I’d been separated hours before, when the Angels first jumped off the stage and into our laps.

I didn’t suffer at Altamont; like a lot of other people, I had a particularly bad time, but once home I was ready and eager to forget all about it. The murder of Meredith Hunter made that impossible; at the same time, the murder crystallized the event. A young black man murdered in the midst of a white crowd by white thugs as white men played their version of black music—it was too much to kiss off as a mere unpleasantness. For the year that followed, not a day passed when I didn’t think about Altamont. I stopped listening to rock and roll and bought a lot of country blues records. Somehow Robert Johnson’s songs contained Altamont; those of the Stones deflected it, just as they had done in the moments before I finally left the place. Johnson’s music was calming and ominous at the same time, and that was just what I wanted: a mood to get myself out of the past and into a future to which I was hardly looking forward.

In the middle of the day at Altamont, as a refugee from the front ranks of the crowd, I met Marvin Garson, the founder of San Francisco’s finest underground newspaper, the Express Times, called by then the Good Times, reflecting a shift from politics to vibe-ism. Marvin had transformed himself into a Ranter some months previously (the Ranters were a loosely organized group of Antinomians who emerged in the middle of the seventeenth century in England, resurfacing 150 years later as a body of Primitive Methodists; their basic tactic consisted of shouting down priests and other pillars of the established order). Marvin was very good at Ranting, and this day, he was crowing: “What an ending! What an ending!” “To what?” I asked. “The Sixties?” “No, no!” he cried. “To my book!”

In terms of cause and effect there was little more to Altamont than that. It did not in and of itself “end” anything. Rather, as Robert Christgau has said, it provided an extraordinarily complex and visceral metaphor for the way things of the Sixties ended. All the symbols were marshaled, and the crowd turned out, less to have a good time than to help make counterculture history. The result was that the counterculture, in the form of rock and roll, Hell’s Angels (“our outlaw brothers,” as many liked to call them), and thousands of politicized and unaffiliated young people, turned back upon itself. No one knew how to deal with a spectacle that from the moment it began contradicted every assumption on which it had been based, producing violence instead of fraternity, selfishness instead of generosity, ugliness instead of beauty, a bad trip instead of a high. Only the music kept its shape—in fact, driven on by the fear and danger of the day and the moment, the music, as the Stones played it, achieved a shape more perfect than it had ever taken on before. Take that for what it’s worth.

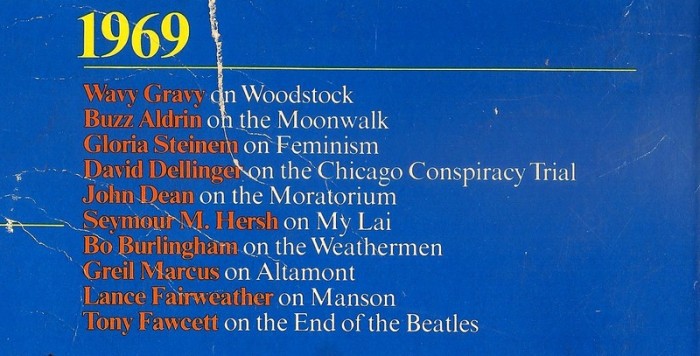

From The Sixties: The decade remembered now, by the people who lived it then (a Rolling Stone publication), 1977

When it was announced,a few days before the “concert”, that Hells Angels- doubtlessly replete with their characteristic swastikas-would be the “security”, anyone with any remaining atom of common sense circulating in their brains,could foresee the outcome…a rock and roll hellhole…the day Murray the K rolled over in his grave……….

Pingback: Black Woodstock and the Opposite of Woodstock – Professor O'Connell's Music History Blog: Assignments, Readings, and Random Thoughts on Music and History Both Inside and Outside the Classroom

Pingback: Rolling Stones Tour Film Gimme Shelter es un clásico de Rock Doc sin respuestas fáciles – CRA Modas

Pingback: Rolling Stones Altamont Banquet - The Woodstock Whisperer/Jim Shelley